Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear

What is it?

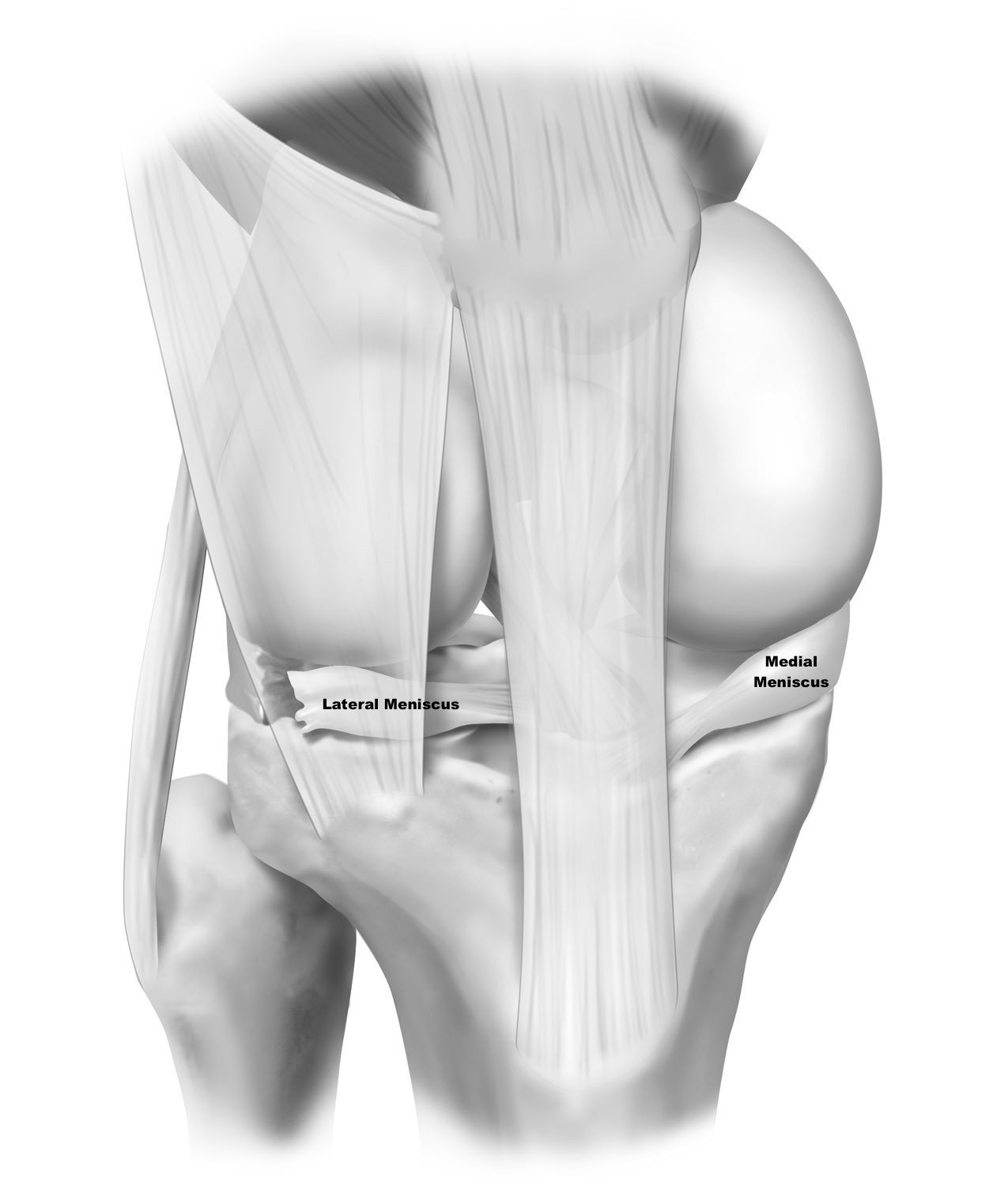

An ACL tear is an injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in your knee. The anterior cruciate ligament is an intra-articular ligament, meaning, it’s located inside the knee joint. There are two intra-articular ligaments of the knee and two extra-articular ligaments that are located outside of the joint. The ACL functions as the primary restraint to anterior (forward) translation (movement) of the tibia. It acts as a seatbelt if you will, primarily exerting its action during more high energy or dynamic motions. The ACL also acts as a secondary stabilizer against excessive rotation, namely internal rotation of the tibia.

How does it get hurt/damaged?

The ACL is injured usually in response to significant force, or energy that forces the tibia (shinbone) too far forward. Often times, this is during sporting or athletic events when someone tried to stop abruptly or change direction. Think of a jump stop in basketball, or a juke move by a running back in football. The momentum and energy of the tibia is continuing in a forward direction and the ACL functions as a seatbelt to prevent excess anterior movement. However, excessive anterior translation then results in an ACL rupture.

Another common way to injure the ACL is a mechanism called the pivot shift. This is a combination of a couple positions and forces that act upon the knee simultaneously. The knee falls into a knock kneed (valgus) position, and simultaneously sustains internal rotation and anterior translational forces. This causes the tibia to be rotated and sublux (move) out the front, thereby tearing the ACL. This is common particularly for younger female athletes during activities like landing for a rebound, or landing from spiking a volleyball.

What are risk factors?

There are a number of both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for sustaining an ACL injury.

Modifiable factors include:

Muscular strength and tone: Patients who are more quadriceps-dominant are at higher risk. Strengthening programs that focus on the hamstrings and gluteal muscles can be very beneficial.

Neuromuscular coordination: Learning how to properly land, slow down, or change direction all can help minimize the forces that go through the knee.

Sporting activity: Higher velocity and more dynamic sports are higher risk.

Bodyweight: Higher body weight leads to higher loads through the knee joint and thereby higher forces on your ligaments, cartilage, bones, etc.

Bony alignment: Patients who are malaligned tend to be at higher risk of ACL injuries. Namely being knock kneed, or having an increased posterior tibial slope, which is a fancy way of saying the top of your tibia tilts backwards more than average, thereby increasing the risk the tibia will translate anteriorly. This can be modifiable, however it requires surgical intervention and is therefore a much bigger task than the others listed above. Bracing can also be utilized, however it does not correct the issue, but helps to minimize risks associated with the malalignment and subsequent overload.

Non-modifiable factors include:

Sex: ACL injuries are more common in younger female athletes. Some of this is due to risk factors previously discussed, as female athletes tend to have stronger quadrciceps than hamstrings, and tend to land with their knees in valgus (knock kneed) which both increase ACL risks.

Hypermobility: Double jointed is a term often used for those patients who can bend their elbows the opposite way, or put their forearms on the ground when bending over to touch their toes. This increased flexibility often comes at a heightened risk for joint instability and ligament tears of the knee, due to the body and the knee specifically easily being manipulated into compromising positions.

How common is an ACL tear?

Very common! Approximately 300,000 people tear their ACL per year in the USA.

When should you be worried about an ACL tear and what should you do initially?

If you hear or feel a pop, or have a sudden giving way of your knee, plus knee effusion (swelling in your knee) — these are concerning signs.

Ice, and elevate the knee and call to be seen by local doctor/orthopedic surgeon. If you are a young high school/college athlete that has access to an athletic trainer (ATC), go in to see them as soon as you are able. ATCs are incredibly knowledgeable and can help get your workup and treatment started.

What is the severity of the injury and the treatment options?

ACL injuries are traditionally graded from 1-3, with 3 being a complete injury. The extent of the ACL injury is important because it can help guide the treatment recommendations of the ACL specifically, however, sometimes what is more important is the associated injuries including: the meniscus, the cartilage surfaces, the anterolateral ligament, and other major ligaments and tendons. An isolated ACL injury is completely different, both from a treatment standpoint, as well as a prognostic indicator, than an injured ACL that has other associated injuries. This is why it is important not to compare ACL injuries with others. No two ACL injuries are the same, so it’s important for patients to speak with their medical team and their family to make sure everyone understands what the injury is and what the treatment options are.

In regards to the ACL injury specifically (the other injuries are covered in other subsections), there are three main treatment options:

Conservative treatment including physical therapy and bracing. This is largely reserved for patients who have sustained isolated ACL injuries that are either partial tears, or sometimes complete tears in patients who are not interested in returning to high demand, high energy sporting activities.

ACL repair, or to maintain the native ACL with sutures, biologic augments and scaffolds to help the ACL heal. This treatment option is gaining traction especially now that we improved techniques and ways to help augment our repairs biologically to help them heal, such as through the BEAR impant. (Read about our first BEAR Implant here!). What makes a good candidate for a repair versus reconstruction is very nuanced and complex topic that is best discussed with your surgeon, but some aspects most surgeons consider are; a) degree of the tear, b) location of the tear, did the ligament tear off its bony attachment, or did it tear in half, c) age of the patient, and d) activity level and sport of choice.

ACL reconstruction, or to replace the ACL with a new piece of tissue either from elsewhere in the patient (autograft) or from a donor (allograft). The conversation on what kind of graft/technique is very nuanced, however, autograft (or taking your own tissue) is usually considered gold standard. The three main grafts used are: a) patellar tendon, b) quadriceps tendon, and c) hamstring tendons.

What is my recovery timeline and the anticipated outcome?

A patient’s rehabilitation timeline is very dependent upon the surgery undergone, what other concomitant injuries they have, and other patient factors. For example, a patient who has a meniscus root tear, treated concurrently with an ACL tear, will likely be non-weight bearing for up to 6 weeks, where a patient with no meniscus tear will potentially be allowed to put weight on their leg immediately. Important in a patient’s recovery journey is not to compare yourself to others, but to stay focused on treatment and goals. While the early timeline and checkpoints vary, the final return to play, or time to being cleared with no restrictions, is likely nine months to one year. The range is dependent on both patient factors as well as usually on strength numbers and tests performed in physical therapy, which allow us to know when your body is ready to return.

In regards to expected outcome, the goal is to get you back to full activity with no restrictions. That means back to scoring touchdowns, goals, shredding fresh powder, or whatever other activities you love.